William A. Martin • Martha’s Vineyard’s Only Documented African American Whaling Captain

Each February, Black History Month calls us to recover stories history allowed to slip quietly beneath the surface. On the cape and islands in Martha’s Vineyard, one such story belongs to William A. Martin—a man whose life traces an extraordinary arc from enslavement and folklore to authority on the open sea.

“From inherited bondage to command at sea, William A. Martin’s life charts a rare and powerful course in American maritime history.”

The genealogy of America’s enslaved people is notoriously difficult to trace, yet fragments of record allow us to glimpse the lineage from which William A. Martin emerged. It is believed that one Sharper Michael, born in 1742 in Chilmark at the home of Zaccheus Matthew to an enslaved African woman named Rose, was Martin’s great-grandfather. Sharper Michael is remembered as the first known person from Martha’s Vineyard killed in the Revolutionary War, struck by a musket ball fired from the British privateer Cerberus in September 1777. Through his relationship with a woman known as Rebecca—or “Beck”—Howosswee, this lineage continued.

That inheritance passed through Rebecca Amos Martin, believed to have been born in Guinea, West Africa, and enslaved by Cornelius Bassett of Chilmark. She may previously have been married to Elisha Amos and bore three children: Pero, Cato, and Nancy. Nancy Martin—William’s grandmother—became one of the most recognizable and enigmatic figures in Edgartown.

Born in 1772, Nancy Martin, widely known as “Black Nance,” lived on the margins of acceptance yet at the center of local lore. The Vineyard Gazette described her as fond of children and attentive to their needs, noting that “few among us…at some time have not been indebted to her.” At the same time, sailors believed her incantations could bring good or bad luck to long voyages, and her “strange power and influence” endured until her death in late 1856.

William A. Martin was born in Edgartown on July 17, 1830, and raised largely by his grandmother and his unwed mother, Rebecca Ann Martin, whose life was marked by poverty, alcohol, and periodic incarceration. Dukes County jailhouse records reflect the instability of those years, and as a result young William was widely known in the community long before he ever sailed.

Edgartown in the mid-nineteenth century was a rough, international port filled with sailors from across the United States and Europe. Education followed the rhythms of the sea: boys learned navigation; girls learned sailmaking. Martin attended the Edgartown School and learned to read and write—an uncommon achievement for a Black child nearly twenty years before the Civil War. Literacy likely led to his early selection as a ship’s log keeper, a role requiring trust, accuracy, and discipline.

Martin went to sea as a teenager, signing on as a greenhand aboard the Benjamin Tucker in 1846. Over the next 44 years, he participated in 14 whaling voyages and captained four of them. Those voyages produced an estimated $1.2 million in revenue from the capture of approximately 22 whales. Martin may have earned as much as $120,000 over his career—an average of about $2,727 annually—far exceeding the wages of most laborers and even skilled tradesmen of the era.

The whaling industry, brutal and often deadly, was one of the few American occupations where skill could outweigh race. Influenced in part by Quaker ideals, maritime communities such as Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard allowed limited opportunities for Black and Indigenous men to advance. By the 1880s, Martin had established himself as one of only a handful of whaling captains of color in the United States.

On July 2, 1857, after a three-plus-year voyage aboard the Europa, Martin married Sarah G. Brown of Chappaquiddick. Sarah was mostly Black and part Wampanoag. Her parents traced their lineage through enslavement, Indigenous heritage, and domestic service in Edgartown households. Between voyages, the Martins lived on Chappaquiddick on land designated for Native people. Despite widespread poverty documented in an 1861 report to the Governor on the condition of Indigenous communities, they owned a modest two-story home—an uncommon achievement for a Black family of the time.

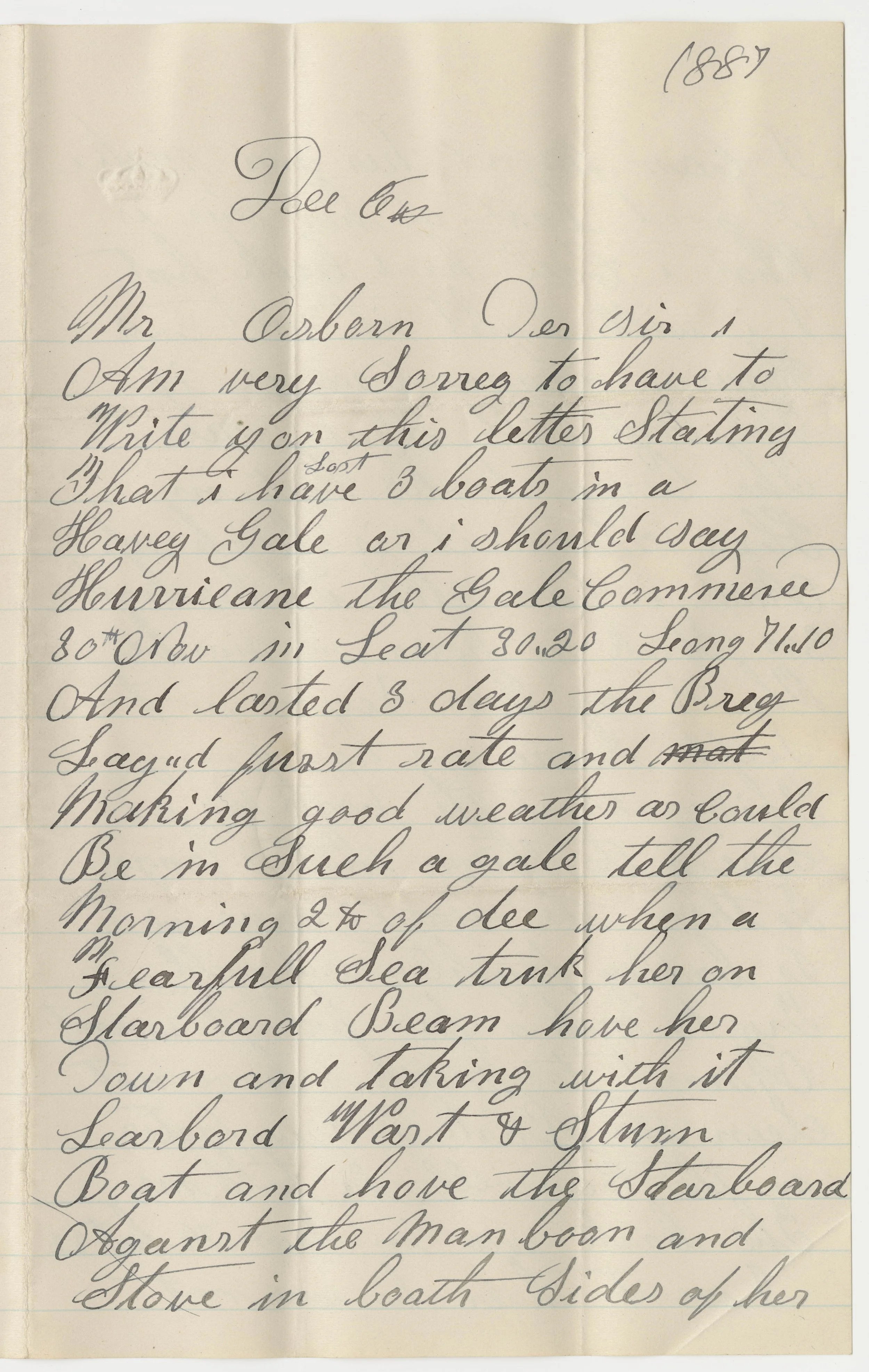

Martin’s final voyage as master came in 1887 aboard the Eunice H. Adams, sailing from New Bedford to the North Atlantic. The journey was difficult and ended badly, closing his seafaring career on a hard note. While respected as a competent captain, Martin did not amass great wealth. His home on Chappaquiddick—still standing today—was modest compared with the grand homes of white captains across the harbor in Edgartown.

In July 1907, an article in the Vineyard Gazette wrote about William and Sarah Martin’s fiftieth wedding anniversary, praising his whaling skill and listing the ships he had commanded. The article noted that Captain Martin had been paralyzed for seven years. He died later that year and was buried alongside Sarah in the Chappaquiddick Cemetery.

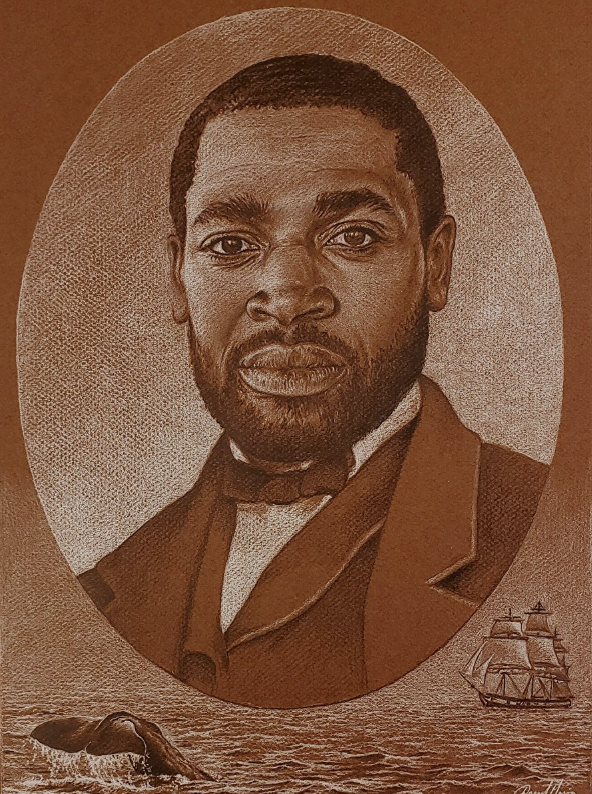

With the decline of whaling and the rise of leisure craft, Martin’s story faded from public memory. It resurfaced through research conducted for the African American Heritage Trail of Martha’s Vineyard. Because no known images of Martin survive, artist Darrel Morris created a reconstructed portrait as an homage to all whaling captains of color whose faces history failed to preserve. William A. Martin stands as one of the most compelling—and long overlooked—figures in the maritime history. He rose from a childhood shaped by poverty and prejudice to become the Island’s only documented African American whaling captain, a position that required exceptional navigational skill, leadership, and trust in an era defined by racial barriers.

William A. Martin’s life—shaped by enslavement, superstition, literacy, labor, and leadership—connects Martha’s Vineyard to a broader maritime lineage that includes Absalom Boston of Nantucket, Paul Cuffe of New Bedmorford, and William T. Shorey of San Francisco. His story reminds us that Black history on the Cape and Islands was not peripheral to maritime success—it helped steer it.

Beyond navigation and command, William A. Martin also possessed notable artistic talent. A drawing of the house in which Sarah and Captain Martin made their home appears in the journal and logbook he kept during the 1853 voyage of the Europa, when he served as First Mate and Keeper of the Log. The drawing is remarkable for its accuracy, and throughout the same log Martin filled page after page with elaborate illustrations of whales—sometimes six or seven on a single page—revealing a practiced and expressive hand. It is believed that the house depicted was Sarah Brown’s family home prior to their marriage.

Above the drawing, Martin wrote:

“Farewell to thee for a time

Days lingering sun is over

this heart will never awaken it

to one bright moment more the hope

……… cherished here within

day by day through life’s flow.”

Sources & References

• African American Heritage Trail of Martha’s Vineyard

• Dukes County Jailhouse Records

• Cape Cod Times

• New Bedford Whaling Museum

• Reconstructed portrait – William A. Martin by Darrel Morris – Nicolson Whaling Collection

• Vineyard Gazette Archives